Ornithology

| Ornithology | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Life Science | ||||||

| Category | Study | ||||||

| Event Information | |||||||

| Participants | 2 | ||||||

| Approx. Time | 50 minutes | ||||||

| Impound | No | ||||||

| Eye Protection | None | ||||||

| Latest Appearance | 2022 | ||||||

| Forum Threads | |||||||

| |||||||

| Question Marathon Threads | |||||||

| |||||||

| Official Resources | |||||||

| Division B Website | www | ||||||

| Division C Website | www | ||||||

| Division B Results | |||||||

| |||||||

| Division C Results | |||||||

| |||||||

Ornithology is a Division B and Division C life science event revolving around the study of birds. The event revolves around competitors assessing their knowledge of information about specific species, classes, and families of birds as well as questions about general bird anatomy. Species that can be used in the event are given through the Official Bird List, a supplemental page in the rules manual behind the rules for the event itself. However, some tournaments (including regional and state tournaments) may use a modified bird list which may have added local birds or a shorter range of testable species and/or families.

Questions that can be asked on the test include questions about life history, distribution, range, diet, behavior, anatomy and physiology, habitat characteristics, and conservation and interactions with humans, although test writers are not limited to these topics. Teams are commonly also asked to participate in identification of species through pictures, characteristics, or calls or sounds made by the species. Therefore, repetition of scientific and common names is common on exams, although these types of questions cannot surpass over 50% of the exam content.

The event is run over 50 minutes and up to two competitors are allowed to compete from a given team. The competition is commonly assessed as stations, a model where students rotate through various locations in a room or pages in an online test an answer questions only visible to that station for a given time (such as two minutes). When the time for that station is complete, students will move to the next station and repeat the process until fifty minutes are up. There are usually 15-20 stations per test, and 4-7 questions per station. Some tournaments (especially online tournaments) opt to use one complete test rather than stations, where students have the entire 50 minutes to answer questions. Students are allowed to bring a binder with rings of 2" or less diameter, a field guide, and an unannotated copy of the bird list provided in the rules. Teams may not remove pages from their binder.

Ornithology rotates with Forestry, Entomology, Invasive Species, and Herpetology every 2 years for both Division B and Division C. It was an event for 2010 and 2011, rotating out for Forestry in 2012. However, the event returned for the 2020, 2021, and 2022 seasons. The event rotated for three years recently due to the effect of COVID-19 on the 2019-20 season.

Overview of the Event

This event may take the form of timed stations or slides, quizzing competitors over the study of birds. Identification and scientific knowledge are equally important in this event, and questions on either may show up on a test. All birds on a test should be either on a state-specific list posted prior to the competition or the 2020 Official Bird List. Identification questions can be to any level indicated on the Official Bird List, and competitors should study the call of any bird marked with a musical note.

Stations (or PowerPoint slides) may include:

- Live/preserved specimens

- Skeletal material

- Recordings of songs

- Slides or pictures of specimens

Each team may bring one published field guide, one 2" or smaller three-ring binder with notes in any form and from any source, all contained in the binder, and the unannotated, unmodified two page Official Bird List. The bird list does not need to be attached to the binder. Both the field guide and three ring binder can contain tabs, sheet protectors, lamination and tabs.

Questions about the birds may be about any of the following topics:

- Life History

- Distribution

- Anatomy

- Physiology

- Reproduction

- Habitat characteristics

- Ecology

- Behavior

- Habitat

- Symbiotic relationships

- Trophic level

- Adaptive anatomy

- Bill size and shape

- Feet size and shape

- Migration

- Distribution

- Conservation and occurence (common, rare, endangered, etc.)

- Diet

- Behavior

- Conservation

- Biogeography

Glossary

| Word | Definition |

|---|---|

| Altricial | When a hatchling is completely dependent on its parents. |

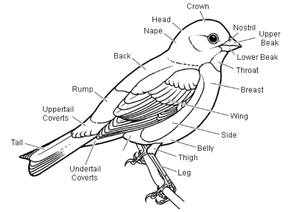

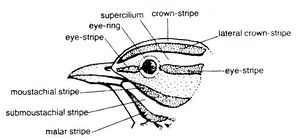

| Bird Topography | The external anatomy of birds; anatomical features that can be observed on the outside of a bird's body. |

| Contour Feather | Any of the outermost feathers of a bird, forming the visible body contour and plumage. |

| Down | A layer of fine feathers found under the tougher exterior feathers. |

| External Anatomy | See Bird Topography |

| Feather (n) | Any of the light horn-like epidermal outgrowths that form the external covering of the body of birds and that consist of a shaft bearing on each side a series of barbs which bear barbules which in turn bear barbicels commonly ending in hooked hamuli and interlocking with the barbules of an adjacent barb to link the barbs into a continuous vane. |

| Feather (v) | To grow feathers. |

| Feather Tract | See pterylae |

| Horns | Paired contour feathers arising from the head. |

| Lower Mandible | The lower part of the bill. |

| Plumulaceous | Downy; bearing down. |

| Precocial | Hatching fully developed, ready for activity, not completely dependent on parents. |

| Pterylae | Areas of the skin from which feathers grow. |

| Upper Mandible | The upper part of the bill. |

General Information

Birds are bipedal, warm-blooded vertebrates that make up the class Aves. They are distinguished from other organisms by feathers which cover their body, bills, and often complex songs and calls. All extant (non-extinct) birds have forearms adapted for flight known as wings, though some species have evolved to the point where their wings are vestigial and no longer used for flight. Birds also have highly specialized respiratory and digestive systems, also adapted to assist with flight. Their respiratory systems are highly efficient, and are one of the most complex respiratory systems of known animal groups.

Birds reproduce by laying eggs, unique for their hard shell made mostly of calcium carbonate. These eggs are laid in a nest, which differs highly from species to species. Some birds construct elaborate, highly specialized nests, while others simply dig out a spot in the ground. The amount of eggs in a clutch can vary wildly from species to species, as well as the time that it takes eggs to incubate.

There are around 10,000 known species of birds, which are found all over the earth, and on every continent. Birds occupy a large range of habitats, making them the most numerous tetrapod vertebrates. While many birds share common characteristics, they are a highly diverse group of animals and their behavior can be very distinct.

Bird Anatomy and Physiology

Topography

Topography refers to the external anatomy of a bird. These are traits that would be easy to identify in a picture, such as the beak, breast and wing. Knowing the parts of a bird can help distinguish differences between species - while two birds may look very similar, one may have a trait that another does not. For example, all members of the family Anatidae have a hard plate known as a nail at the tip of their beak. This nail serves a different purpose depending on the species, but its presence indicates what family an organism is a part of. Investigating a bird's topography can also give hints about the bird's habitat and diet, as most birds are highly adapted to their surroundings. A bird with a small, pointed beak may eat primarily insects, but a bird with a long, narrow beak may drink nectar or probe into the ground for food.

Physiology

Respiration

A bird's respiratory system is one of the most efficient found in vertebrates. This is mainly because of their ability to fly, which creates a need for more oxygen.

Air sacs are structures unique to birds. Taking up 20% of a bird's internal body space, air sacs store air, keeping a fixed volume in the lungs. There are two types of air sacs: anterior and posterior. Sometimes, air sacs rest inside the semi-hollow bones of birds. In addition, a bird's lungs take up half of the space that a mammal's lungs do, yet weight does not decrease.

When a bird takes a breath, air passes through the trachea either into the bird's lungs and then the anterior air sacs or directly into the posterior air sacs. The air in the anterior air sacks go directly through the trachea and back out of the nostrils, while the air in the posterior air sacs go through the lungs, and then through the trachea as the bird exhales.

One important adaption of birds is that new oxygen and old, waste gasses are never mixed during respiration. Old air is almost completely replaced by new air when a bird takes a breath.

Circulation

Like many mammals (including humans), birds have a four-chambered heart. However, a bird's heart can be almost twice the size of a mammal's, and much more efficient, for the same reason as the circulatory system. Powerful flyers and divers have the largest heart relative to their body size.

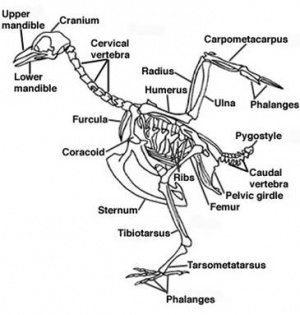

Skeleton

A bird's skeleton is, in many ways, well-adapted for flight. The major bones of a bird's skeleton have a hollow interior with crisscrossing "struts" to provide support. Some bones contain air sacks that are used by the respiratory system. Bird skeletons generally follow a specific format, with the exception of extreme specialization.

The image above shows the bones in the average bird's wing, with the left side being the tip of the wing and the right side being where it connects to the bird's body. Notice how similar it is to a human arm. There are two major sections to the arm: the upper arm is made up of the humerus, while the lower arm consists of the radius and the ulna. Birds have 2 wrist bones (carpals). However, instead of having 5 metacarpals (hand bones), they have one bone called the carpometacarpus. This limits the mobility of the manus but makes it better adapted for flight. Birds have 3 digits and 4 finger bones (phalanges, singular phalanx). The middle and largest digits have two phalanges.

Birds' legs are slightly more complicated. What most people think of as the knees of a bird are actually the ankles, as the knees (and the upper legs (femur)) are mostly hidden by feathers. Birds have a fuse and extended foot bone (tarsometatarsus) which most people think of as the lower leg, and which give birds three sections to the leg instead of 2. The bone in the actual lower leg is the tibiotarsus, a fusion of part of the tarsus with the tibia. Birds have (at most) four toes, although some birds have less (e.g. the ostrich, which only has two toes. Refer to the image at the right for leg anatomy, and the image below for toe variations.

- Anisodactyl feet have three toes forward and one backward. They are the most common toe configuration and is used by songbirds and perching birds.

- Zygodactyl feet have two toes forward and two toes backward. They are used by climbers such as woodpeckers because it enables a stronger grip on branches.

- Heterodactyl feet are similar to zygodactyl ones except the second toe is reversed. They are only found on trogons.

- Syndactyl feet have the third and fourth toes partially fused together. They are characteristic of Kingfishers.

- Pamprodactyl feet have all four toes facing front. Swifts may use this configuration to get a better grip when hanging on the sides of chimneys or caves.

Feathers and Plumage

Birds are the only modern animals that have feathers. Feathers are made of beta-keratin, which also makes up the scales on bird's legs.

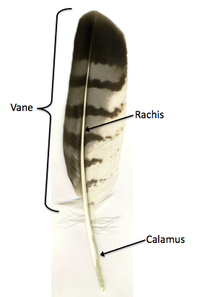

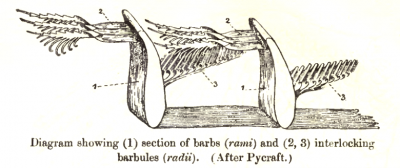

Contour feather - Any of the outermost feathers of a bird, forming the visible body contour and plumage. A contour feather consists of a middle shaft and a vane on both sides of the shaft. The calamus, or quill, is the base of the shaft, while the rachis supports the vanes.

The vane of a contour feather is mainly made up of barbs, which consist of rami (s. ramus) sticking out vertically from the rachis. Each ramus contains barbules, which in turn have interlocking barbicels. This gives the vane of a contour feather a tight, smooth surface.

Flight feathers - These feathers are only found on the wings and the tail. They are large, stiff, and aerodynamic, which is helpful in flight. There are three main types of flight feathers: primaries, secondaries, and tertiaries. In addition, feathers called coverts cover the bases of the flight feathers.

Down feather - A feather that has plumulaceous barbs. It is mostly used for insulation. Down feathers do not have a rachis; barbs are attached directly to the quill.

Semiplumes - Feathers with a long rachis and plumulaceous barbs. Like down feathers, semiplumes mainly provide insulation.

Filoplumes - Small feathers with a long rachis, but only a few barbs at the top. Filoplumes are attached to nerve endings at the base, letting them send information to the brain about the placement of contour feathers.

Bristles - Stiff feathers with some barbs found at the base. Bristles are almost always found on the face of birds. Bristles have many possible applications, including protection from insects and dust, and acting as a "net" to aid in catching insects.

Species of Birds

This section contains information about individual orders, families and species. The birds are in the same order as they are on the Official Bird List. One order of birds was removed completely from the Official Bird List in 2020 - Trogoniformes. Images of each bird, as well as comments on their identification, can be found on the complete bird list.

- Anseriformes

- Galliformes

- Gaviiformes

- Podicipediformes

- Procellariiformes

- Pelecaniformes

- Suliformes

- Ciconiiformes

- Falconiformes

- Accipitriformes

- Cathartiformes

- Gruiformes

- Charadriiformes

- Columbiformes

- Cuculiformes

- Strigiformes

- Caprimulgiformes

- Apodiformes

- Coraciiformes

- Piciformes

- Passeriformes

Bird Calls

| Order | Family | Species | Common Name | Link | Mnemonic/ID Tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anseriformes | Anatidae | Cygnus buccinators | Trumpeter Swan | Call | oh-OH, like a trumpet |

| Anseriformes | Anatidae | Anas platyrhynchos | Mallard | Call | quack-quack-quack, stereotypical duck |

| Galliformes | Phasianidae | Bonasa umbellus | Ruffed Grouse | Call | thumping noise when drumming, also a chicken-like pita-pita-pita |

| Galliformes | Odontophoridae | Colinus virginianus | Northern Bobwhite | Call | bob-white in a rising whistle |

| Gaviiformes | Gaviidae | Gavia immer | Common Loon | Call | a deranged, eerie, rising scream |

| Ciconiiformes | Ardeidae | Botaurus lentiginosus | American Bittern | Call | pump-er-lunk like dripping water |

| Accipitriformes | Accipitridae | Haliaeetus leucocephalus | Bald Eagle | Call | feeble, high whinnies |

| Accipitriformes | Accipitridae | Buteo jamaicensis | Red-tailed Hawk | Call | ker-wee, or stereotypical eagle sound in a movie |

| Gruiformes | Rallidae | Porzana carolina | Sora | Call | sor-a or ker-wee, also a loud descending whinny |

| Gruiformes | Gruidae | Grus americana | Whooping Crane | Call | beeping bugle calls, sound like squeaky toys |

| Charadriiformes | Charadriidae | Charadrius vociferus | Killdeer | Call | high-pitched, fast, repeating kill-deer |

| Charadriiformes | Laridae | Leucophaeus atricilla | Laughing gull | Call | raucous, jeering laughter |

| Columbiformes | Columbidae | Zenaida macroura | Mourning Dove | Call | coo-OO, oo, oo, oo, sound a bit like a voice crack, often mistaken for owls |

| Cuculiformes | Cuculidae | Coccyzus erythropthalmus | Black-billed Cuckoo | Call | toot-toot-toot like a recorder, all on the same pitch, sometimes cu-cu-cu-cu-cu |

| Strigiformes | Strigidae | Bubo virginianus | Great Horned Owl | Call | who's awake? me too, stereotypical owl |

| Strigiformes | Strigidae | Strix varia | Barred Owl | Call | who cooks for you? who cooks for you all?, sound a little deranged/laughter-like |

| Caprimulgiformes | Caprimulgidae | Caprimulgus carolinensis | Chuck-will’s-widow | Call | fast, bubbly "chuck-will’s-widow" |

| Apodiformes | Trochilidae | Archilochus colubris | Ruby-throated Hummingbird | Call | monotonous, squeaky chee-dit, wings can sound like an insect's |

| Coraciiformes | Alcedinidae | Megaceryle alcyon | Belted Kingfisher | Call | dry, mechanical rattle like a fishing reel |

| Piciformes | Picidae | Colaptes auratus | Northern Flicker | Call | high rolling rattle that sound like really fast seagull calls, squeaky kyeer |

| Passeriformes | Tyrannidae | Myiarchus crinitus | Great Crested Flycatcher | Call | whee-up, sweeping upward |

| Passeriformes | Corvidae | Cyanocitta cristata | Blue Jay | Call | jeer jeer jeer, car alarm noises |

| Passeriformes | Corvidae | Corvus brachyrhynchos | American Crow | Call | caw! (what were you expecting?) |

| Passeriformes | Paridae | Poecile atricapillus | Black-capped Chickadee | Call | scolding chick-a-dee-dee-dee, thin whistle of hey-sweetie, phoebe song |

| Passeriformes | Paridae | Baeolophus bicolor | Tufted Titmouse | Call | nasal peter-peter-peter, keep-her |

| Passeriformes | Sittidae | Sitta canadensis | Red-breasted Nuthatch | Call | nasal hank-hank-hank like a horn |

| Passeriformes | Troglodytidae | Thryothorus ludovicianus | Carolina Wren | Call | teakettle-teakettle, faster and more bubbly than common yellowthroat |

| Passeriformes | Turdidae | Hylocichla mustelina | Wood Thrush | Call | ee-oh-lay, high and clear |

| Passeriformes | Turdidae | Turdus migratorius | American Robin | Call | cheerily, cheer up, cheer up, cheerily, cheer up, also a horse-like whinny, alarm call a high pitched scream |

| Passeriformes | Mimidae | Mimus polyglottos | Northern Mockingbird | Call | mimics sounds two or three times, then switches, call a sharp chack |

| Passeriformes | Parulidae | Geothlypis trichas | Common Yellowthroat | Call | witchety-witchety, slower and squeaker than carolina wren |

| Passeriformes | Emberizidae | Pipilo maculatus | Spotted Towhee | Call | drink-your-tea, dry and raspy, also maaaaw |

| Passeriformes | Cardinalidae | Cardinalis cardinalis | Northern Cardinal | Call | birdie-birdie-birdie-birdie like an alarm |

| Passeriformes | Icteridae | Agelaius phoeniceus | Red-winged Blackbird | Call | conk-la-ree, also a short check |

| Passeriformes | Icteridae | Sturnella neglecta | Western Meadowlark | Call | thin and flute-like, it's-a-complicated-song |

| Passeriformes | Icteridae | Icterus galbula | Baltimore Oriole | Call | pure whistle, dear-dear, come-right-here, dear |

Former Calls

Competitors were formerly required to know these calls, but as of 2020 these calls are not on the Official Bird List.

Former Calls

|

ID tips

A few pointers on often-missed species. Don't worry about being confused if you're brand new; it'll start to make sense the more time you spend looking at images of these birds.

- Eastern Kingbird is more banana-shaped, and eastern phoebe is like a teardrop with a tail. Eastern Kingbird also has a white band at the tip of its tail and Eastern Phoebe has more blurred outlines.

- Cooper’s Hawk has a tell-tale tail banding pattern.

- Brown Thrasher is the lankiest with longer tail, legs, and beak. It has yellow eyes. For ovenbird, look for the orange and black headstripes, a warbler silhouette, or gray-green cheeks the same color as its back. Wood thrushes have the outlines of American Robins and mottled/black cheeks.

- Common Nighthawk has white on its wings, while Chuck-will's-widow has a larger and flatter head.

- Ravens are bigger than crows, have shaggy throat feathers, and have wedge-shaped tails. Crows are smaller, have smooth throats, and have square tails.

- Red-throated Loon looks more delicate and haughty, while Common Loon’s bill looks heftier and sturdier.

- Because American woodcock has eyes closer to the backs of their heads, they look derpier than Wilson's Snipes. American woodcocks have horizontal white lines on their heads, while the Wilson's Snipe has vertical white lines.

- Olive-sided Flycatcher has an olive “vest” or sides, while Great Crested Flycatcher has highlighter belly, brown fluff on its head, and cinnamon tail.

- If it’s a closeup, the best field mark is CA condor’s “boa.” Far away, condor has white “arms” while Turkey Vulture has black ones.

- Common Ground-dove has a scalier head than Mourning Dove.

- Barn Swallow has a red forehead and a notched tail, while Cliff Swallow has a white/yellow forehead and a rounder tail.

- Grebe heads look more like triangles, while loons’ look like rectangles.

- Northern Mockingbird, when singing, repeat each snippet about 3 times and seem to mimic car alarms a lot.

- For gulls and terns, look at their bills. Tern (very sharp, angled wings, pointy tails): Caspian is red, Black is black, Least is Yellow. Gulls(taller, chonkier, and lack tail points): Herring has red spot, Laughing is black, and Ring-billed is yellow (unless it’s super brown and has long neck, in which case may be juvenile Herring)

Field Guides

Teams may bring one commercial field guide (no other books) to assist at competition. Each box below contains information on a specific field guide, aiding in the choice of which one is right for competition. A field guide is a personalized choice, and different competitors have different needs. There is no "one size fits all" book that is best for competition - a balance should be achieved between identification and information. A guide optimized for identification may have detailed photos of each bird, such as the Sibley Guide to Birds. A guide optimized for information may not have as many pictures, but might have a paragraph or two relating to habitat, reproduction, etc. like the National Geographic field guide. The layout and size of a field guide are also important factors - a well organized guide can make identification much easier. However tabs, labels, and practice can assist with accessing information regardless of the layout of the guide. Guides should also contain most if not all of the birds on the national list. If a bird is missing, then it could be a disadvantage if a question about it comes up on a test. Obtaining two contrasting field guides to compare could also be a useful strategy in order to determine which one is the most helpful in a specific situation.

Remember that a field guide is an important decision, but it can also be supplemented with other materials. Competitors may write in or tab their field guide, adding information as needed. The field guide is also not the only resource available - each team may have one 2" or smaller three-ring binder. A choice in field guide depends largely on personal preference, strengths and weaknesses.

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America

|

The Sibley Guide to Birds

|

Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America

|

National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America

|

Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America

|

Additional Field Guides

|

Other books

While only commercial field guides may be brought to competition, other books can be used to study. Each book below has a link to its Amazon page.

- The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior As the companion guide to The Sibley Guide to Birds, this book is very helpful and easy to study from. The book is split into two sections: the first provides information about general ornithology, while the second includes more specific info about each family of bird. Both sections are very easy to read and understand. Strongly recommended.

This is a college level textbook that contains lots of information about many topics in ornithology. It gets to be very in-depth and contains much more information than what you actually need in the competition, but it is a great resource for accurate information.

Sample Questions and Answers

What is the difference between precocial and altricial young?

Answer

Precocial youung are born with open eyes and down. They are capable of leaving the nest within 2 days of hatching. Altricial young are born with closed eyes and no down. They rely on parents for survival. All passerines are altricial.

|

What is the purpose of lobed feet?

Answer

They allow birds to walk across marshes by increasing surface area, but provides more toe maneuverability than webbing. Coots and Grebes have lobed feet.

|

Describe three abilities that are unique to hummingbirds.

Answer

Hummingbirds drink nectar, can hover and fly backwards, and their tiny legs and feet make them incapable of walking.

|