Anatomy/Digestive System

The digestive system is a topic of the event Anatomy and Physiology. It is part of the event during the 2018 season, along with the respiratory system and immune system.

For a list of secretions in the digestive system, see the Digestive Secretion List.

Overview and Functions

The goal of the digestive system is to process or digest food in the body. Food is any material consumed for nutrition. It provides the body with essential molecules and elements that can be utilized elsewhere in the body. There are four main processes that occur in this system - ingestion, digestion, absorption, and elimination. Ingestion is the taking in of food, and digestion involves breaking it down. Absorption moves the food into the bloodstream, though it does not involve actually taking those absorbed nutrients and making them a part of the body. The usage of the absorbed molecules is known as assimilation. Finally, waste is removed from the body through elimination.

The digestive system is made up of two groups of organs - those in the alimentary canal and accessory organs. Members of the alimentary canal include the esophagus and the intestines. These organs make up the continuous tube that passes from the mouth to the anus. Accessory organs such as the salivary glands and the pancreas provide aid to those organs in the alimentary canal by producing enzymes or performing other actions.

Summary of the Digestive Tract

The digestive tract is about 8 meters, or 28 feet, long. It can take 15 to 72 hours for food to pass from the mouth to the anus.

The mouth is where the digestion of food starts. The mouth is a good example of mechanical digestion and chemical digestion at work. The teeth chomp, chew, and tear food down into smaller pieces (mechanical digestion). The molecular structure of the food does not change in mechanical digestion. Then, the salivary glands secrete saliva into the mouth, breaking down starches into dextrin and maltose (chemical digestion). Saliva is a form of chemical digestion because it changes the molecular structure of the food. These digestive processes create food boluses.

After food boluses are developed in the mouth, they go down the pharynx. The pharynx is a shared connection between the nasal cavities, the mouth, the air tract, and the esophagus. Therefore, there must be a structure to prevent the boluses from entering the trachea (passage to the lungs). This is why we have an epiglottis. The epiglottis is a small flap which can open and close the entrance to the trachea. When food boluses travel through the pharynx, the epiglottis folds down to protect the airway. However, in instances such as talking or eating, the epiglottis can get confused. In order to talk, the epiglottis must be open. In order to swallow, the epiglottis must be closed. Therefore when attempting both tasks, the epiglottis might malfunction and this could result in choking.

After the pharynx, food bolus is transported to the stomach via the esophagus/oesophagus. The esophagus is a muscle-walled tube that goes from the throat to the lower digestive tract. To help food get down, muscular contractions called peristalsis push food down towards the stomach. To demonstrate peristalsis motions, imagine a sphere in a rubber tube. The diameter of the sphere is a little more than the diameter of the tube. To move the ball out, one would squeeze the tube from one end, and slowly move his/her hand towards the ball while squeezing to push it out. The reason peristalsis is important is when digestion is working against gravity. For example, when eating upside down, the food bolus is still able to move to the stomach because of peristalsis contractions.

Next in the digestive tract comes the stomach. When we think of digestion, the first thing that comes to mind is the stomach. It acts like a waiting room for food bolus. While the food boluses are waiting, the stomach breaks the food down into a liquid-like mixture by churning the food (mechanical digestion) and secreting gastric acid (chemical digestion). Gastric acid also kills bacteria that may be in the food.

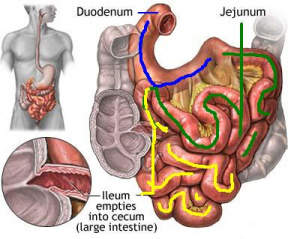

When food boluses are ready to be further digested, they transfer to the duodenum by contractions of the stomach walls. The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine and is about 25 cm in length. The duodenum is stationary and is fixed behind sheets of connective tissue called peritoneum. Glands in the duodenum secrete a thick alkaline fluid that counteracts the acidic nature of the chemicals the food bile has absorbed. The gallbladder also secretes pancreatic juice and bile into the duodenum.

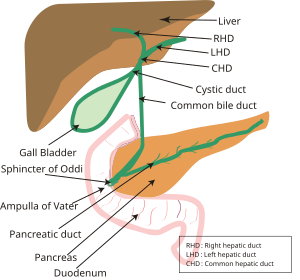

The liver is a very important part of the digestive system, even though food does not directly pass through it. The liver produces bile (a greenish fluid which aids in the digestion of fats), which is stored in the gallbladder. When bile is needed, it joins with secretions from the pancreas and goes through the common bile duct into the duodenum.

After the duodenum comes the two other parts of the small intestine, the jejunum and the ileum. These are what make up the bulk of the small intestine. The jejunum is the first part while the ileum is the second part. Here, food boluses are digested even further, and some nutrients are absorbed through the walls. The ileum is the longest portion of the small intestine.

After passing through the duodenum, jejunum, and the ileum (the small intestine), food bolus makes its way through the large intestine. The large intestine is actually shorter than the small intestine, but larger in diameter. Water and electrolytes are removed in the large intestine. Also, microbes such as bacteria aid in further digestion. Finally, food bolus comes out of the anus as feces.

In-Depth Descriptions

The Oral Cavity

The oral cavity is another name for the mouth. It is the first part of the digestive tract.

- The lips, formed by the orbicularis oris muscles, help in food intake and determining temperature of food.

- The buccinator muscles assist in the process of mastication, or chewing. Mastication is the first process of digestion.

- The tongue, a large muscle, helps move the food around the oral cavity. It also is necessary in swallowing. Swallowing is also called deglutition.

- The surface that forms the top of the oral cavity is called the palate. It is split into two parts.

- The hard palate is the most anterior section. It contains bone. This is often referred to as the "roof of the mouth".

- The soft palate is more posterior. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. It helps by preventing food from entering the nasal cavity.

- The tonsils are part of the lymphatic system. They are tissues to the right and left of the mouth.

- The uvula is also part of the lymphatic system. It is an extension of the soft palate, and is hanging down from it. The uvula is often wrongly referred to as the tonsil.

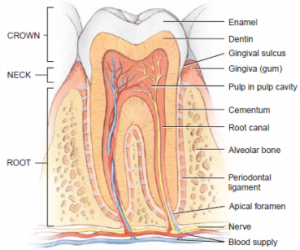

Teeth

The teeth chew and break down the food mechanically. An child has 20 deciduous teeth while an adult has 32 permanent teeth. There are four types of teeth: Incisors, canines, premolars, and molars.

Teeth consist of the crown, the neck, and the root.

- The crown is the upper surface of the tooth. Bumps on the crown are called cusps.

- The neck is the region under the crown, but above the alveolar bone.

- The root is the region inside the alveolar bone.

Salivary Glands

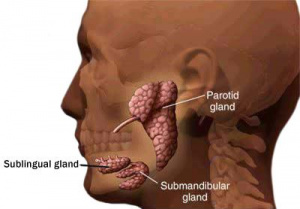

The salivary glands produce saliva, which is secreted into the oral cavity. There are two types of salivary glands: serous and mucous. Serous saliva is enzymatic, while mucus acts as a lubricant.

There are three pairs of salivary glands: the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual.

- The parotid glands are the largest. They are located slightly posterior to the cheeks and make 25% of the saliva, though this amount rises to 50% when eating. They are serous.

- The submandibular glands are below the mandible bone and make up 70% of salivary production. They produce more serous saliva.

- The sublingual glands are the smallest and make 5% of the saliva. They are below the floor of the oral cavity. They produce mostly mucus.

The Pharynx

The pharynx is often referred to as the back of the throat. Food pieces, now called bolus, travel from the oral cavity to the pharynx in the process of deglutition, or swallowing. The pharynx is also a shared passageway, connecting the nasal cavity, oral cavity, air passageway, and epiglottis. There are certain structures inside the pharynx to conduct the movement of air and food.

- During deglutition, the soft palate elevates to prevent food from entering the nasal cavity.

- Another structure, the epiglottis, bends down to prevent food from entering the air passageway.

- If the epiglottis fails to function, food bolus may be lodged in the air passageway (choking).

The Esophagus

After food bolus passes through the pharynx, it goes through the esophagus, or oesophagus. The esophagus is directly under the pharynx. There is no defining structure that separates the pharynx from the esophagus. The esophagus is about 25 cm long in adults.

Muscular contractions called peristaltic waves propel food down the esophagus. This is why food can still travel through the esophagus while the body is lying down or even upside-down.

The Stomach

The stomach is the first part of the gastrointestinal tract. Its main purpose is to store and churn food.

- The layers, from innermost to outermost, are the mucosa (made of simple columnar epithelium), submucosa, oblique muscle (helps churn food), circular muscle (helps churn food), longitudinal muscle (helps churn food), and serosa (reduces friction between stomach and neighboring body parts).

- There are three main sections to the stomach: the fundus, the body, and the pylorus. The fundus is the top part of the stomach, or the roof. The body is the bulk of the stomach. The leftmost region is the pylorus.

- The texture of the inner surface of the stomach largely depends on how much food bolus it contains. If it does not contain much food bolus, the stomach is small and the inner surface has lots of folds. These folds are called rugae. If the stomach does contain lots of food bolus (like after a meal), the stomach is bigger and rugae are not present.

The Small Intestine

The small intestine is the next part of the digestive tract. The small intestine is about 6 meters long, and so it is the longest part of the digestive tract. Its main purpose is the digestion of food and absorption of nutrients. The small intestine consists of three sections: The duodenum (25 cm), the jejunum (2.5 m), and the ileum (3.5 m).

The layers are, from innermost to outermost, the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis - circular, muscularis- longitudinal, and serosa.

The mucosa has four major cell types:

- Absorptive cells digest and absorb food

- Goblet cells produce mucus

- Granular cells protect from bacteria

- Endocrine cells produce regulatory hormones

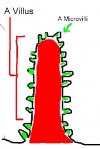

Since digestion only occurs at the surface, there must be a lot of surface area for effective digestion. To increase surface area,the small intestine has circular folds, villi, and microvilli. Villi are tiny finger-like projections. Microvilli are even smaller finger-like projections that are on the villi.

Chyme moves through the small intestine with two types of contractions.

- Peristaltic contractions propel chyme forward. They are similar to the contractions in the esophagus.

- Segmental contractions mix chyme by squeezing in outward motions. NOTE: Segmental Contractions DO NOT help move food through the GI tract.

The differences between the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum are as follows:

- A gradual decrease in diameter (from duodenum to ileum)

- a gradual decrease in thickness of intestinal wall

- a gradual decrease in number of circular folds

- a gradual decrease in number of villi.

Only the ileum contains Peyer's patches, which are clusters of lymph nodes.

Accessory Organs

The liver and gallbladder, along with the pancreas, are classified as accessory organs. However, they are not simply fashion garments. The accessory organs of the digestive tract are vital to the processes of the digestive system.

The Liver and Gallbladder

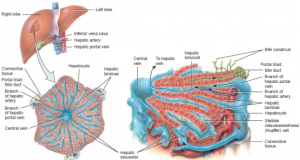

The liver weighs about three pounds and is on the right-hand side of the body, right beneath the diaphragm. It is divided by the falciform ligament. The liver is attached to the underside of the diaphragm by the coronary ligament. The liver contains 4 lobes, right, left, caudate, and quadrate.

The liver is a part of more than one anatomical system. As well as functions associated with the digestive system, the liver also stores nutrients, cleans blood, and makes blood proteins. However, because this is the digestive page, we will be focusing on the digestive functions. The liver can also regenerate itself. This is useful because if one part of someone's liver is surgically removed (if they have cancer), the liver can regrow itself and there would be no need of having a liver donor. The ability for it to regenerate is very important because as it filters out blood, it comes into contact with many different chemicals which can damage liver cells.

The main function of the liver is the production of bile. The liver produces and secretes about 700 mL of bile every day. The groups of cells that produce bile are called hepatocytes. Bile helps make fat digestion easier by breaking fat particles into smaller, more manageable ones. This is called emulsification. Bile is stored in the gallbladder until it is needed. The gallbladder also concentrates the vile by removing the water from it. Then, it is transported to the duodenum. Note that bile is NOT a digestive enzyme, it emulsifies fat. Bile also contains bile salts, these are critical for digestion of fats.

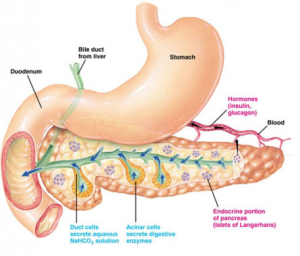

The Pancreas

The pancreas is an accessory organ that secretes enzymes into the duodenum. It is located underneath and a little to the left to the liver. It is made up of endocrine and exocrine tissue. The endocrine tissue produces hormones, and the exocrine tissue produces digestive enzymes.

The digestive enzymes are created by acinar cells in the pancreas. Secretions of the pancreas travel through the pancreatic duct and join the common bile duct. They enter the duodenum through the duodenal papilla. (Check the Digestive Secretion List for a list of pancreatic secretions.)

The pancreas also produces hydrogen carbonate (HCO3-) which helps counter the acidic quality of chyme that enters the duodenum from the stomach. This stops pepsin digestion but makes the other secretions of the pancreas more effective.

The Large Intestine

The large intestine is the final part of the digestive tract. It is about 5 feet long, and consists of the cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal. Note that it is shorter than the small intestine. The reason it is called the large intestine is that it's wider than the small intestine. The large intestine is mobile, and undergoes several muscular contractions called mass movements. Mass movements propel the colon towards the anus to help move food along with peristalsis. Note that the large intestine generally does not absorb nutrients. Although some nutrients such as vitamin K are absorbed, the main site of nutrient absorption is the small intestine. The large intestine mainly only absorbs water and salt.

The Cecum

The cecum, or caecum, is the first part of the large intestine. Food from the small intestine enters the cecum through the ileocecal valve.

A small pouch-like attachment to the cecum is the appendix. The appendix has no real function, as it was probably lost through human evolution. Organs that have no real function like the appendix are referred to as vestigial organs. Scientists believe the appendix was used to digest a diet with a lot of cellulose (plant fiber). Today, the appendix may store helpful bacteria. This is important because if an infection infects the large intestine, and all of the helpful bacteria were gone, the appendix could move some of the good bacteria from itself to the large intestine.

The Colon

The colon makes up the bulk of the large intestine. There are three parts to the colon- the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon, and the sigmoid colon. The ascending colon is the first part, being right after the cecum. Food travels upwards through it. Next is the transverse colon. Food travels from left to right. Then, food goes down through the descending colon and sigmoid colon.

The colon is where chyme is converted to feces. Water and salts are absorbed in the large intestine, and microorganisms such as helpful bacteria help break down components of the feces. The colon stores the feces until defecation, where the feces is transported out of the digestive tract through the anus.

The inner wall of the large intestine is lined with mucus. It also has straight, tubular glands called crypts that have goblet cells to produce the mucus. Longitudinal, smooth muscle does not have its own layer in the large intestine. Instead, it exists in the form of three strips called teniae coli. Attached to the outer wall are small fatty sacs called appendices epiploicae.

The Rectum and Anal Canal

After food travels through the sigmoid colon, it enters the rectum. The rectum is a straight, muscular tube. The muscle layers are very thick to push food into the anal canal. The anal canal is the last 2-3 centimeters of the digestive tract. The anal canal has an even thicker muscle layer.

The peritoneum is a serous membrane that surrounds the abdominal cavity and organs. The inner layer is called the visceral peritoneum, and the outer layer is called the parietal peritoneum. A double layer of peritoneum is called mesentery.

Regulation of Digestive Secretions and Processes

This section is incomplete. |

Digestive secretions are regulated by the parasympathetic nervous system and exocrine and endocrine hormones.

Regulation of Stomach

Initiation of digestion is mostly driven by the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). When the vagus nerve is stimulated, gastric secretions begin.

Digestion, Absorption, and Transport of Nutrients

Digested molecules of food and water, as well as minerals from the diet, are absorbed throughout the small intestine. These molecules pass through the mucosa via absorptive cells. Lipids are absorbed last of the three main food groups, since they must first be broken down by lipase and bile salts. (See also: Mineral Absorption)

Diseases of the Digestive System

There are many different diseases and disorders that affect the digestive system. In the subcategories below describe how the disease or disorder affects the body, from the cellular level up to the entire organism. The first six diseases/disorders are required for all levels, with the remaining 4 being necessary for the national level competition only.

Stomach and Duodenal Ulcers

Ulcers occur when the mucus in the stomach or the intestines deteriorates, leaving the flesh directly exposed to the acid contained in these organs. Ulcers can also occur in the esophagus, but the focus is on the stomach and intestines.

These ulcers can occur for several reasons:

- (60% of stomach, 90% of duodenal) A bacteria, Helicobacter pylori, inflames the tissue by living in the mucus.

- An extreme intake of either sour or spicy foods with a high acid content.

- The use of NSAIDs may also play a role in this condition. NSAIDs block the body's ability to make more mucus, thus the mucous layer breaks down, giving the gastric acid an exposed portion of the skin.

Ulcers can be either benign or harmful, with most duodenal ulcers being benign.

Ulcers can be treated by using common drugs. Avoid smoking and drinking, as both inhibit healing of the ulcers.

Cancers of the Digestive System

If a tumor affects the digestive system, it is called a neoplasm. These neoplasms can occur in a variety of places in the system, including the esophagus, stomach, small intestines, and colon. There are several variations of cancer in each of these sub-groups, listed in their appropriate section below.

Esophageal (Oesophageal) Cancers

There are two major types of cancer occurring in the esophagus, as the other types are exceptionally rare. There are:

- Squamous cell cancer (approximately 90%-95% of all cases, worldwide)

- Adenocarcinoma (fastest growing in the United States, responsible for most of the rest of the approximately 5%-10%)

There are several major symptoms of esophageal cancers. They include vomiting blood, regurgitation of food, heartburn, difficulty swallowing, and having chest pain that has nothing to do with eating.

Tests include:

- Barium swallow (must swallow a drink containing barium, then x-rays are taken to look for any abnormalities in the travel of the liquid)

- chest MRI (used for determining the progression of the cancer)

- endoscopic ultrasound (also used for the progression of the disease)

- esophagogastroduodenoscopy (use of a small camera inserted through the mouth to view the tissue in the throat, stomach, duodenum)

- biopsy

- PET scan (used to determine stage of disease/whether surgery is possible to remove cancerous growth).

For these cancers, surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation are the most common treatments. Chemotherapy and radiation are most often used to help reduce the cancer to a point where surgery can be used, or to help reduce the symptoms (the latter case is generally when the cancer is considered incurable).

Stomach Cancers

Stomach, or gastric, cancer is defined as a cancer that develops in the lining of the stomach. There are a number of factors that influence a person's vulnerability and likelihood to develop this form of cancer, but some of the most important are:

- The presence of Helicobacter pylori in the stomach, or ulcers caused by this bacteria, and surgery performed on any such ulcer (accounts for approximately 60% of all cases)

- Smoking

- Anemia

- Long-term gastritis

- Obesity

- A diet high in salted and/or pickled foods

- Heavy drinking (severe alcohol abuse usually results in gastric lining damage)

- Genetics (hereditary forms account for 10 to 13% of all cases)

- Long-term use of NSAID's (Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)

When the cancer is in early stages, the symptoms seem rather innocuous, appearing as indigestion, nausea, heartburn, bloating, and/or a loss of appetite. As the cancer progresses, the symptoms often become far more severe, including, but not limited to, moderate to severe stomach pain, blood in stool, weight loss, vomiting, continued bloating and heartburn, and yellowing of the eyes and skin.

An overwhelming majority of cases of gastric cancer are classified as carcinomas, meaning the cancer develops in the epithelial tissue inside the stomach. However, other forms of cancer, such as lymphomas, may arise in other portions of the stomach, but are considered far rarer. Because the initial symptoms are similar to that of many lesser diseases, the warning signs are usually passed off as the ill effects of a food or a virus. Stomach cancers tend to develop slowly over a period of several years as a result.

There are several tests or examinations performed to determine if a patient has a form of gastric cancer. The most common is a gastroscopic examination (upper endoscopy), using a camera attached to a wire to view the inside of the stomach. Other common diagnosis methods are an Upper GI series and various CT (computed tomography) scans of the abdominal region. Biopsies are also commonly used to determine the malignancy of the tumor. A new method, utilizing a breathalyzer-like device, is being developed by Chinese and Israeli scientists, with a successful clinical study performed in 2013-2014.

Treatment methods remain very few and ineffective for gastric cancers. Surgical removal of the tumor is the most effective manner of treatment, with chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapy mostly being used to reduce the size of the tumor and provide palliative care. Survival rates for stomach cancer are extremely low (five-year survival rate is below 10%) for several reasons. First, this particular form of cancer is primarily found in geriatric patients (median age of presentation is between 70 and 75 years of age). Also, by the time symptoms are attributed to something serious, the cancer has generally metastasized.

Other interesting facts about stomach cancer:

- Occurs twice as often in males as in females

- 5th leading cause of cancer

- 3rd leading cause of death from cancer

- Before 1930's, since most food was pickled or salted before refrigeration was developed, it was the most common cause of cancer-related death.

- Most commonly found in East Asia and Eastern Europe. (Much less common elsewhere)

Colorectal Cancers

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known by various other names (such as colon cancer, bowel cancer, and rectal cancer), refers to the neoplasms affecting the lower portion of the large intestine, which is known as the colon, and the rectum. A majority of colorectal cancer cases are a result of the lifestyle of the patient. Factors include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Age (geriatric patients are at higher risk)

- Race (people of African descent are at higher risk)

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Sedentary lifestyle (exceptionally low levels of exercise)

- Excessive consumption of red or processed meats

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and IBS (irritable bowel syndrome)

- Genetic disorders such as familial adenomatous polyposis

Symptoms for this form of cancer include rectal bleeding, blood in stool, unexplained weight loss, a change in bowel movements (either constipation or diarrhea) that lasts for four or more weeks, and weakness or fatigue that is unexplained. A large portion of patients reported no early signs or symptoms for the disease, so regular screening past 50 years of age is recommended. Because more than 80% of colorectal cancer cases arise from a certain form of polyp called "adenomatous polyps," regular screening can pick up these early indicators up to 2-3 years before symptoms even begin to appear.

There are several testing methods, but the most common include:

- Fecal Occult Blood Testing (FOBT)

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy

- Colonoscopy

- Multitarget stool DNA screening test

In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, testing is organized for all persons older than 50. In the United States, it is recommended that those at high risk start regular screening at 40, and those with normal risk begin at 50, but no organized testing is performed nationwide.

The treatment methods for colon and rectal cancer vary slightly from each other, in part due to the difference in physiology between the two areas, and also how they react to the treatment types. If caught early on, the cancer is removed by laparotomy (a cut in the abdomen) to remove the cancerous section, and the colon is reattached. If the tumor takes up, or has spread to, a large portion of the colon, a colostomy may be necessary. If the tumor is larger, chemotherapy is used to shrink the tumor before surgery. Radiation therapy is generally not used in any stage of colon cancer due to the sensitivity of the lower intestine to radiation. The major difference in treatment between rectal and colon cancer is the use of radiation in second stage (and higher) tumors for rectal cancer, since the sensitivity is much lower in that region. Palliative care is usually the only course of treatment if the cancer has progressed to an advanced stage, especially for colon cancer. After successful removal of a tumor, the patient is encouraged to exercise quite regularly, as there is some evidence that indicates that exercise reduces the risk of re-emergence of cancer.

Interesting facts about colorectal cancer:

- Drinking 5 or more glasses of water a day is linked to lower risk for these cancers

- The five-year survival rate is below 60% but the rate is approximately 100% if caught in the M0 stage or earlier, and approximately 90% if caught in the T1 or T2 stages.

- Metastasized colorectal cancer usually spreads to the liver and then the lungs

- In 2012, 1.4 million people were diagnosed with new cases

- 65% of all cases are found in developed countries

Diarrhea

Also spelled diarrhoea, this condition occurs when an individual has three or more loose or liquid bowel movements in a day. If this condition is prolonged, it can lead to severe dehydration, and even death in some instances. For this reason, a patient with diarrhea should be given fluids, especially in the form of clean water, on a regular basis. Very young and elderly patients should be monitored closely with this condition, as diarrhea affects them more severely.

Diarrhea can be utilized by two major parties: the host's own body in attempting to fight off infection, and also by the pathogen attempting to harm the host. Because of this, it is often important to determine the cause of the issue before prescribing or self-medicating with antidiarrheals.

Symptoms associated with diarrhea include, but are not limited to:

- Loose and/or watery stools

- Pain or cramps in the abdomen

- Bloating

- Nausea

Lactose Intolerance

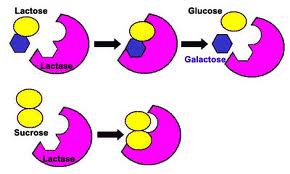

Lactose intolerance is the digestive system's inability to break down a sugar called lactose, hence the name. This most commonly occurs due to the body's lack or insufficient quantities of an enzyme, called lactase, used to break the lactose for energy. As a result, the person with this condition will experience pain because of their body's inability to digest the sugar. Most infants have a proper amount of lactase enzymes inside their bodies in order to break down the lactose found in their mother's milk. However, as they age, the amount of active lactase dramatically decreases in most cases. Lactose intolerance is the human normal, with lactose "tolerance" being a rather new human evolution, especially in those of Northern European descent. People with lactose intolerance should avoid consuming dairy products. A lactase pill can be ingested in order to receive the enzyme lactase needed to digest dairy products.

Hepatitis

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver caused by a virus or high alcohol consumption. There are multiple forms of hepatovirus, including: A, B, C, D, E, and F. Hepatitis can cause many complications such as liver cirrhosis, cancer, and death.

Hepatitis A: This is a very contagious viral disease caused by the hepatitis A virus. It is very rare but it can be spread by contaminated food and water. The virus spreads by the fecal-oral route. It can also be spread by contact with someone who has the virus. Only humans can transmit the virus. Some symptoms include flu-like symptoms and jaundice. This disease is preventable by vaccine. It can also be prevented by good hygiene and sanitation. It can clear up in about 1-2 months with rest a hydration.

Hepatitis B: It is a dangerous liver infection. In the early stages, it is inflamed. In the late stages, cirrhosis occurs. Cirrhosis is when liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue. It spreads by sexual contact and it can easily be preventable by vaccine. The condition can clear up on its own. However, chronic cases may require medication and possibly a liver transplant. Some symptoms include jaundice and dark urine. It is easily preventable by absences or no sexual activity.

Hepatitis C: It is an infection of the liver that is caused by the hepatitis c virus. It is spread by contaminated blood. This can occur by unsterile tattoo needles or dirty needles used by a hospital. Some symptoms include loss of appetite and jaundice. It is diagnosed by blood testing got antibodies or viral RNA. It is easily preventable by using sterile blood equipment. There is no vaccine against this virus. It can be treated by using medications such as antivirals.

Hepatitis D: It is a liver disease that is caused by the hepatitis D virus. It occurs only among people who are infected with the Hepatitis B virus. It can be prevented by sexual absence. Essentially, the same technique as preventing the hepatitis b virus (above). Symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, and fatigue. There are few treatments for it.

Hepatitis E: It is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis E virus. The liver gets inflamed. It is usually spread by contaminated water(contaminated by fecal matter). Symptoms include but are not limited to jaundice and lack of appetite. Hepatitis E usually goes away in about 4-6 weeks.

Hepatitis F: This is a hypothetical virus. Several Hepatitis F cases came in the 90's but none of them had substantial evidence.

Appendicitis

Sometimes, the appendix may become infected and inflamed, a condition called appendicitis. Appendicitis is tested by touching the McBurney's point on the patient. This is located about 1/3 away from the left pelvic bone to the belly button. If the McBurney's point is extremely sensitive to the pressure, there is a good chance the patient has appendicitis. Appendicitis can be treated in most cases with an appendectomy, where the appendix is removed.

Diverticular Disease

Diverticular disease is a general term used to describe the experience of symptoms related to diverticula (small bulges or pockets that develop in the intestine). Diverticular disease is related to two other conditions called diverticulosis and diverticulitis. All of these conditions affect the large intestine, especially the portion closest to the rectum which is called the sigmoid colon.

Diverticula are considered a normal part of aging, as most people develop them later in life. Doctors and health institutions estimate that approximately 5% of the population have developed diverticula by age 40, and over 50% by age 80. The exact cause of these bulges has not been determined yet, but there is a strong correlation between low fiber, high red meat diets and the development of the pockets (but not solid evidence). Other factors include:

- Smoking

- Obesity (and even just being overweight)

- History of constipation

- Long-term use of NSAIDS (i.e. ibuprofen, etc.)

- Family history of developing diverticula before age 50

The symptoms most often associated with diverticular disease, before it progresses to diverticulitis, include:

- Abdominal pain, usually in the lower quadrants

- Bloating

- Long-term changes in bowel movements (constipation and/or diarrhea)

- Episodic constipation followed by diarrhea (a pattern often described as going to the bathroom repeatedly but only passing rabbit pellet stools)

Because these symptoms are generally minor and often not very painful, this disease is usually diagnosed during other tests. Only approximately one in every four people who develop diverticula experience symptoms such as the ones listed above. However, if the symptoms do appear to persist, and the doctor deems it necessary, typically a non-invasive test will be ordered to look for a source. These exams include CT scans, X-rays, and an ultrasound.

Treatment for this disease is generally not necessary, as the symptoms are not harmful, unless a complication is found during testing. A diet high in fiber and low in red meats is recommended to reduce the risk of more diverticula forming. Also, it is necessary to avoid the use of laxatives to treat the condition, and use of enemas should be reduced.

Diverticulosis

The overwhelming majority of people that have diverticula have no noticeable symptoms whatsoever, and the diverticula do not affect the function of their intestine. This condition is referred to as diverticulosis. In the long run, this condition can lead to the discomfort and other symptoms associated with diverticular disease, and eventually (in some, but not all, cases) diverticulitis. In rare cases, the diverticula can lead to perforation or stricture of the large intestine, fistulas, and rectal bleeding. For a more in-depth discussion of these symptoms, see the diverticulitis symptoms and complications section below.

Because diverticulosis does not normally present with any symptoms, there is no standard testing. Usually, the diverticula are discovered during any number of other routine tests for cancer or other diseases, such as a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. There is no treatment necessary unless a complication is found during a test, though a diet high in fiber and low in red meats is recommended. It is also necessary to avoid intake of laxatives if diagnosed with this condition, and enemas are to be used infrequently.

Diverticulitis

As the name of the condition indicates, diverticulitis is when the diverticula become inflamed. This inflammation is thought to be caused by either a small perforation of one of the diverticula that the body is able to heal, or an infection of bacteria inside the bulge in the colon, although an exact cause is not currently known. Diverticulitis usually presents after the minor, more generalized, symptoms of diverticular disease. Risk factors that correlate to a likelihood to develop diverticulitis are essentially the same as diverticular disease. These include a diet low in fiber and high in red meat, smoking, being overweight or obese, a history of constipation, long-term use of NSAIDS (i.e. ibuprofen, naproxen, etc.), and a family history of developing diverticula before age 50.

The symptoms of diverticulitis are often far more severe than those of either diverticular disease or diverticulosis, and a number of secondary issues can occur, leading to complicated diverticulitis (referring to the complications). Some symptoms and potential complications include:

- Severe abdominal pain, usually more noticeable and painful on the left side

- A fever of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (approximately 38 degrees Celsius) or higher

- Severe diarrhea

- Rectal bleeding

- Formation of a stricture (when a section of the colon narrows that prevents stool from passing through easily)

- Formation of an abscess (basically a pocket of pus sealed off within the colon)

- Formation of a fistula (this occurs when the diverticulum forms a connection with another organ or the skin). Commonly occurs with the fistula tract leading to the bladder. Other potential sites include the uterus, vagina, skin, or another portion of the intestine.

- Peritonitis (literally the inflammation of the peritoneum, which is the membrane tissue covering and surrounding the organs in the abdomen)

GERD

GERD (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease) is a disease in which the contents of the stomach travel back up the esophagus, irritating the lower esophageal area (and sometimes the upper area too) and causing a sensation described as "heartburn" which is worsened by eating or lying down. GERD is caused by a dysfunctional lower esophageal sphincter (LES) which would typically function to close off the esophagus from the lumen of the stomach. Some of the atypical symptoms of GERD include difficulty swallowing, sore throat, and regurgitation of food.

Usually, a diagnosis can be made by a physician with a description of the symptoms which may be followed up by an endoscopy (more specifically, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, or EGD) in which the physician searches for tissue erosions, thickening of the mucosal layer, and possibly ulcers in the esophagus to help confirm the diagnosis. For a more definite diagnosis, a pH monitor is placed over the LES, and the results (characterized by timely decreases in pH, indicating acid reflux) are compared with the patient's description of symptoms according to the time they occur. This is called "ambulatory pH monitoring."

There is no actual cure for GERD, but the symptoms of GERD can be treated.

- For heartburn, antacids can be taken after meals but relief will not last very long. For longer relief, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can be used to reduce the amount of HCl (hydrochloric acid) produced in the stomach.

- Acetaminophen can help relieve pain associated with GERD.

- Problematic foods should be avoided.

Crohn's Disease

Crohn's Disease is a form of IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) which is characterized by chronic inflammation of the GI tract. Although it is usually associated with the large intestine, Crohn's disease can affect any part of the GI tract, as opposed to ulcerative colitis (which only affects the large intestine). It is categorized as an autoimmune disorder. This means that the body's immune system overreacts and starts attacking healthy body cells in the affected areas of the GI tract.

Individuals with Crohn's disease experience chronic pain due to the inflammation which results from the hyperimmune response. Other symptoms include: pain with defecating, fever, diarrhea or constipation, abdominal pain, fatigue, bloody stool, and ulcers anywhere in the GI tract (including the mouth).

The exact cause of Crohn's disease is unknown. Heredity and environment factors have been shown to affect development of the disease. Risk factors include smoking and a family history of Crohn's disease. Crohn's disease can occur in individuals of any age or sex, but it has been observed to be most frequent in men ages 15-35.

There are several methods for diagnosis:

- Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, endoscopy, and enteroscopy to check for physical signs such as strictures and inflammation

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) or CT (Computed Tomography) scan

- Upper GI series (x-rays or the stomach and esophagus) mainly to look for ulcers

- Physical examination may reveal abdominal masses/lumps and tenderness when certain areas are palpated

There is no specific cure for Crohn's disease, although the symptoms can be controlled to some degree by medication and changes in diet. In severe cases, surgery (bowel resection) may be required to remove certain affected areas of the GI tract. Since the cause of Crohn's disease is unknown, there really aren't any known methods of prevention.

Celiac Disease

Also spelled as Coeliac Disease, Celiac Disease is when the body has an immune reaction to gluten and can experience symptoms such as diarrhea or bloating. Also, the villi and microvilli are flat reducing the amount of absorption. It is a reaction to gliadins and glutenins (gluten proteins). The body's immune response attacks the villi in the small intestine, making nutrient absorption harder. Celiac disease is also hereditary. For treatment, people should avoid eating anything with gluten, such as wheat, barley, rye, or any other grains with gluten. This will help with the symptoms and let the intestine heal.

Most people that have Celiac disease have the HLA-DQ2 allele. For the most part, the most effective treatment is not eating gluten (having a gluten-free diet).

Outside References

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons: Diverticular Disease

Mayo Clinic: Colon Cancer

National Health Service (UK): Diverticular Disease and Diverticulitis

Digestive System Disorder And Diseases Colon Diseases