Herpetology

| Herpetology | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Life Science | ||||||

| Category | Study | ||||||

| Event Information | |||||||

| Latest Appearance | 2019 | ||||||

| Forum Threads | |||||||

| |||||||

| Question Marathon Threads | |||||||

| |||||||

| Division B Results | |||||||

| |||||||

| Division C Results | |||||||

| |||||||

Herpetology was an event for the 2019 and 2018 seasons in Division B and Division C that dealt with the identification and life science of different specimens of amphibians and reptiles. It was replaced by Ornithology for the 2020 season.

This article mainly deals with the general concepts of this event. Specific identification info can be found on Herpetology/Herpetology List.

The official taxonomy list used for this event for the 2019 season can be found here. States may also have their own lists, which can be found on the respective state's website.

General Herpetology Knowledge

Amphibians vs. Reptiles

From an evolutionary standpoint, reptiles are considered more "advanced" than amphibians because they evolved an amniotic egg, which contains amniotic fluid to provide moisture to the developing embryo. Thanks to this adaptation, many groups of reptiles were able to sever their ties with aquatic environments and colonize land, unlike their amphibian counterparts.

| Amphibian | Reptile | |

|---|---|---|

| Etymology | "Two lives" | "To crawl or creep" |

| Eggs | Anamniotic: The embryo is surrounded by a vitelline membrane, and the egg is composed of jellylike layers. It has a moist and spongy exterior. | Amniotic: Tough and leathery outer shell, contains amniotic fluid to provide moisture to the developing embryo. |

| Fertilization Method | Internal or External | Internal only |

| Habitat | Generally rely on water | Generally terrestrial |

| Skin | Moist glandular skin | Keratinized, rough skin/scales |

| Origin | Lobe-finned fishes | Amphibians |

| Feet | Often webbed, without claws | Clawed, less often webbed |

| Respiration | Lungs, skin, and/or gills | Lungs, skin in rare cases. |

| Urine Composition | Urea | Most: Uric acids; Turtles: Urea |

Skull Morphology

This event doesn't generally test extremely intricate specifics about amphibian/reptile skull morphology, but students should be familiar with the following major groups:

- Anapsids: The skull has no temporal fenestrae (openings). Turtles, salamanders, and frogs/toads are anapsids.

- Synapsids: The skull has only one temporal fenestra (opening, lower). Mammals, including humans, are synapsids.

- Diapsids: The skull has two temporal fenestrae (openings). Lizards, snakes, and crocodilians are diapsids.

Thermoregulation

All amphibians and reptiles are ectothermic, which means that they rely on external sources of heat to maintain their body temperature. This is also sometimes referred to as "cold-blooded," but this is misleading as the animal's blood is not "cold," but rather they are simply unable to regulate their own internal temperatures.

The alternative to this is endothermy, which birds and mammals exhibit. Endothermic animals can regulate their internal body temperature, and they are not dependent on external heat sources.

| Endothermy | Ectothermy | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

Other thermoregulation-related vocabulary that may be tested in Herpetology includes:

- Heliotherm: An animal that basks in the Sun's heat to regulate its body temperature; Many species of snakes, lizards, and turtles exhibit heliothermy.

- Heterotherm: An animal that can switch between poikilothermic and homeothermic strategies. For example, bats and hummingbirds are homeothermic when active and poikilothermic at rest.

- Homeotherm: An animal that maintains its body temperature at a constant level; Homeotherms are not necessarily endothermic: Many reptiles are considered homeothermic because they use behavioral methods to keep their body temperature constant.

- Kleptothermy: A form of thermoregulation in which an animals share metabolic heat; Animals may huddle together to conserve heat, but kleptothermy isn't necessarily reciprocal. Some male garter snakes produce "trick" female pheromones after emerging from hibernation, causing another male to cover them in an attempt to mate. The male "steals" heat through kleptothermy and uses it to his advantage when trying to find a true mate.

- Parietal Eye/"Third Eye": A light-sensitive structure on top of some lizards' heads that plays a role in thermoregulation.

- Poikilotherm: An animal whose internal temperature varies considerably; The opposite of a homeotherm.

- Regional heterothermy: The ability to maintain different temperature zones in different regions of the body.

- Thigmothermy: Obtaining heat by lying against a warm object, such as the ground; Often seen in snakes, Lacertidae, Scincidae, and Teiidae.

Internal Anatomy

Circulatory System: consists of two loops.

- Pulmonary loop - from heart to lungs and back

- Systemic loop - from heart to body tissues and back

Hearts in all herps other than crocodiles consists of two atria and one ventricle somewhat divided by a septum. Contraction of heart keeps oxygenated and deoxygenated blood separate even though ventricle isn't completely divided. In crocodiles, two atria and ventricles exist.

There are two main ways in which adult amphibians respire:

- Pulmonary respiration - breathing through lung by positive-pressure breathing

- Cutaneous respiration - respiration through the skin

Nervous System: brain is similarly sized (relatively) in amphibians and reptiles.

In reptiles, the cerebrum (used for controlling behavior) is larger than amphibians. Optic lobes are also large, due to the fact that many reptiles rely on sight for hunting. Some reptiles and amphibians have nictitating membrane which is a transparent,movable membrane that covers the eyes allowing them to see with their 'eyelids' closed.

Hearing is also important. Sound waves heat the tympanum and then are transferred to the inner ear through the columella. Snakes lack a tympanum and are effectively deaf. They are however able to sense vibrations caused by sound through a touch. They detect these ground vibrations which are transferred to columella by the bones of jaw.

The Jacobson's organ is an extra sense organ in the roof of the mouth of reptiles. This organ is used to detect scents in the air. Reptiles use their forked tongue to gather chemicals from the environment and transfer it to the back of their mouth. These scent chemicals are then analyzed by the brain to find prey by using the two segments of the forked tongue independently gathering scent, and determining in the brain the direction of the scent through the sensitivity on each fork. While reptiles can smell with their nostrils, the jacobson organ is vastly more sensitive and important.

Another 'sixth' sense is present in pit vipers. A heat-sensitive pit beneath eyes allows the snake to detect heat. This allows them to locate warm blooded prey instantly in any light.

Reproduction

Sexual reproduction involves combining of two sets of genetic material, while asexual reproduction produces genetically identical offspring. All reptiles and amphibians reproduce sexually, with the exception of some parthenogenetic whiptails, geckos, rock lizards, Komodo dragons, snakes, frogs, and toads. Parthenogenesis occurs when eggs can develop without fertilization, and parthenogenetic species are sometimes unisexual, containing exclusively members of one sex.

Fertilization: The joining of egg and sperm

- Internal Fertilization: Fertilized within female's reproductive tract

- Copulation: The union of the male and female sex organs

- External Fertilization: Fertilized outside of the female's body

| Internal Fertilization | External Fertilization | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

Reptilian patterns of reproduction are divided based on how long eggs stay within female and how the developing embryo is provided with nutrition.

- Oviparity: "Typical" egg-laying; Females lay internally fertilized eggs which then undergo an incubation period before hatching.

- Ovuliparity: Females lay unfertilized eggs which males fertilize externally.

- Ovoviviparity: "Halfway" between laying eggs and giving live birth: Eggs develop inside of the female's body and either hatch while still inside of her or very shortly after being laid. Also spelled "ovovivipary" or "ovivipary."

- Viviparity: Live birth: Shell is not formed around an egg, and young mature in female's body while receiving nutrients by placenta.

Reproduction is also characterized by the number of times that an organism reproduces during its lifespan. Iteroparous organisms engage in multiple reproductive events during their lifetime, while semelparous organisms only reproduce once. Nearly all amphibians and reptiles are iteroparous.

Mating systems vary based on how whether males and females mate with multiple partners, differentiated as follows:

- Monogamy: One male mates with one female exclusively

- Polygamy: Any form of non-monogamous mating.

- Polygynandry: Multiple males mate indiscriminately with multiple females

- Polygyny: One male gets exclusive mating rights with several females

- Polyandry: One female gets exclusive mating rights with several males

- Cuckoldry: Mostly in fish, a variant of polyandry dominated by large and aggressive males

Courtship

Courtship refers to behavior performed typically by males with the intention of persuading a female to mate. The following table outlines common courtship behavior in each major group on the Official List:

| Group | Common Behaviors |

|---|---|

| Order Crocodylida (Crocodiles & Alligators) | Females may initiate; Jaw-slaps, roaring/bellowing, dominance, subordination displays, tactile communication such as underwater vibrations of the male's trunk |

| Order Testudines (Turtles) | Some territorial males may fight to establish a dominance hierarchy. Mating typically occurs underwater, and males flutter their forelimbs and claws in the female's face, bite the female's head/neck, and mount her. |

| Suborder Lacertilia/Sauria (Lizards) | Males may do "push-ups," bob their heads, and fight to establish a dominance hierarchy. Male anoles may change color and extend their dewlaps. |

| Suborder Serpentes (Snakes) | Females release pheromones trails for males to follow. Males court females by bumping their chin on the back of the female's head crawling over her. During copulation, the male will wrap his tail around the female's and meet at the cloaca. |

| Order Caudata/Urodela (Salamanders) | Courtship is less elaborate in salamanders, but males and females may stimulate each other's cloacas or wiggle their tails. Some males possess nuptial pads to help grasp females during mating, and others have a hedonic gland to secrete a substance used in sexual attraction/stimulation. |

| Order Anura/Salentia (Frogs/Toads) | Males call to attract females, and the male with the loudest call is most likely to find a mate. Nuptial pads and sticky skin secretions may be present. See below for information about amplexus. |

- Hemipenes: Paired copulatory organs of male snakes and lizards.

Other courtship practices include:

- Sexual cannibalism: A female animal kills and consumes a male before, during, or after copulation, confers fitness advantages to males and females

- Sexual coercion: Males dominate females sexually by force and size.

- Tournament species: Members of one sex (usually males) compete for mates.

- Lekking: Males assembling at a communal breeding location and attract females using competitive displays.

- Mating Ball: Multiple male snakes court one female at once, swarming over her in order to form a ball.

- Natal Homing: The tendency to return to one's birthplace to mate.

- Storing of Sperm: Many females have the ability to store male spermatophores (packets of sperm) in their spermathecae (sperm-storing organs) for months or years, which allows them to delay egg-laying until conditions are suitable and produce eggs with multiple fathers in the same clutch.

Frogs and toads have a unique method of reproduction known as amplexus, which involves the male grasping the female from behind to that the external fertilization is successful. There are two main types of amplexus:

- Inguinal Amplexus occurs when the male grasps the female around her waist, and it is considered to be the more primitive of the two types.

- Axillary Amplexus occurs when the male grasps the female around her armpits, and it is considered more "advanced" from an evolutionary standpoint because it brings the cloacae closer together, which allows for more efficient fertilization.

Eggs

With some exceptions, most amphibians and reptiles have an egg stage in their life cycle. The term "gravid" refers to a female who is pregnant, bearing eggs or developing young. Some lizards, snakes, and crocodilians have a carbuncle or egg tooth, a specialized structure used to break the egg shell from the inside.

A very important differentiation between amphibian and reptile eggs is that reptile eggs are amniotic, which means that provide amniotic fluid to the developing embryo.

Life Cycle

- Heterochrony: Developmental change in the timing or rate of events leading to changes in size and shape

- Neoteny: Delayed somatic development with constant reproductive development, leads to paedomorphism, e.g. larval gills in adult salamanders in axolotls (family Ambystomatidae, Ambystoma mexicanum)

- Progenesis/paedogenesis: Constant somatic development with accelerated reproductive development, leads to paedomorphism

- Paedomorphism: Retention of larval traits of adults

Sex Determination

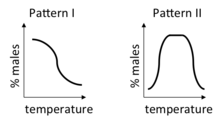

Unlike humans, some reptiles exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD), in which the sex of offspring is not controlled by genetics, but instead by the temperature of the nest during the middle 1/3 of incubation (often referred to as the TSP, or thermosensitive period). TSD is seen in crocodilians, turtles, and some lizards. Scientists are unsure about the evolutionary origin or function of TSD, but two hypotheses include:

- "Phylogenetic Inertia": TSD was present in the groups' ancestor, and it was maintained because it was adaptively neutral.

- Natural selection would favor TSD in developmental environments where one sex has a survival advantage over the other.

Because climate change is causing global changes in temperature, scientists fear that it may be harming the sex ratios of many reptiles, especially sea turtles (family Cheloniidae). Many species with Pattern IA and II (see below) will nest earlier to preserve their sex ratios.

There are three primary types of TSD that are typical of reptiles:

- Pattern IA has a single transition zone, and eggs will hatch males if the temperature is below it and female if the temperature is above it. Most turtles follow this pattern of TSD.

- Pattern IB is similar to Pattern IA, but females hatch if the temperature is below the transition zone and males hatch at temperatures above the transition zone. It is seen in tuataras, lizard-like reptiles endemic to New Zealand which were not on the Official Herpetology List for the 2018-2019 season.

- Pattern II has two separate transition zones. Intermediate temperatures produce mostly males, while females are produced at both extremes. Lizards, turtles, and some crocodilians follow this pattern of TSD.

Hermaphroditism is a condition that occurs when a given individual in a species possesses both male and female reproductive organs or can alternate between possessing first one and then the other, usually sequential from female to male (protogyny), less common for a male to switch to a female (protandry). Reptiles and amphibians are generally not hermaphrodites, and it is important not to confuse hermaphroditism with parthenogenesis. Reptiles and amphibians are most commonly gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious, which means that males and females are distinct organisms.

Behavior

- Fossorial: Adapted to digging and living underground

- Natatorial: Specialized for swimming

- Benthic: Living on the benthos (bottom of an ocean, lake, or river)

- Motile: Having the capacity to move from one place to another

- Sessile/Sedentary: Fixed in one place

Daily Activity Patterns

Because all amphibians and reptiles are ectotherms, much of their behavior is governed by their need to maintain an appropriate body temperature. Many ectotherms have optimum temperatures of function (due to the optimum temperatures of enzymes), which causes many species in cooler habitats to be diurnal (active primarily during the day) and many species in hotter habitats to be nocturnal (active primarily during the night).

| Diurnality | Nocturnality | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

- Torpor: A state of decreased physiological activity, usually by a reduced body temperature and metabolic rate, some reptiles undergo this during short cooling periods, reptiles usually do not undergo this in the winter, mammals undergo this during hibernation

- Crepuscular: Active during dawn and dusk (twilight)

- Matutinal: Active during morning, wake up earlier than diurnal organisms, mostly bees

- Vespertine: Active during evening, wake up at around the same time as nocturnal, become active before nocturnal organisms

Dormancy

- Dormancy: A period in an organism’s life cycle when growth, development, and physical activity are temporarily stopped, minimizes metabolic activity and helps an organism conserve energy

- Predictive dormancy: When an organism enters a dormant phase before the onset of adverse conditions

- Consequential dormancy: When an organism enters a dormant phase after the onset of adverse conditions

- Hibernation: Mechanism used by many mammals to reduce energy expenditure and survive food shortage over the winter, prepares by building up body fat, undergoes many physiological changes including decreased heart rate (by as much as 95%) and decreased body temperature

- Diapause: Predictive delay in development in response to regular and recurring periods of adverse environmental conditions, predetermined by an animal’s genotype

- Estivation/aestivation: Consequential dormancy in response to very hot or dry conditions

- Brumation: Reptiles generally begin brumation in late autumn (more specific times depend on the species). They often wake up to drink water and return to "sleep". They can go for months without food. Reptiles may eat more than usual before the brumation time but eat less or refuse food as the temperature drops. However, they do need to drink water. The brumation period is anywhere from one to eight months depending on the air temperature and the size, age, and health of the reptile. During the first year of life, many small reptiles do not fully brumate, but rather slow down and eat less often. Brumation is triggered by lack of heat and the decrease in the hours of daylight in winter, similar to hibernation. This differs from hibernation because the reptiles do not go into a sleeping state. Originally proposed by Mayhew (1965) “to indicate winter dormancy in ectothermic vertebrates that demonstrate physiological changes which are independent of body temperature.”

Note: Hibernation and brumation are sometimes used interchangeably for reptiles and amphibians.

Conservation

Populations of various reptiles have diminished for several reasons. First of all is their (or their eggs) use as food in many cultures. (Snapping Turtle soup is actually quite tasty.) "Rattlesnake roundups" have occured in some states as recreational activities. Snakes are gathered to be killed by visitors who do so in belief that killing snakes protect public. Every year in Sweetwater, Texas, about 1% of the entire rattlesnake population of Texas is slaughtered. Some attendees claim that this is justified due to the fact that they collect venom, however the venom is useless for most any research as it is not collected in a sterile environment. Some are also gathered for use as folk medicine. Snake venom has use in medical research. Habitat destruction is also hurting various populations.

Amphibian populations have been mysteriously declining for several years. There are several proposed reasons for this decrease. Some believe thinning of the ozone layer increases the amount of UV B radiation that reaches sensitive eggs, embryos, and larvae causing them to die. Herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers also have killed amphibians when interfering with their natural hormones. Habitat destruction and disease have also lead to a large amount of decrease in population.

One of the largest threats to anurans (frogs and toads) is a lethal fungal infection that has been expanding in prevalence and range in recent year. This disease, known as chrytridiomycosis, is caused by the chrytid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. The disease is thought to increase in range with global warming. This disease is responsible for large numbers of frog death, and are among the leading causes of the extinction of several frog species, and possible more to come.

Organizations and Acts

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES): An international agreement among governments

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN): An international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources composed of both government and civil society organizations

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Founded in 1964, it is the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biological species.

- Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA): Designed to enact provisions outlined in CITES, it was signed into law by Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973. It declares the categories E (endangered), T (threatened), C (candidate), ES/A (not endangered but similar in appearance to an endangered species), TS/A (not threatened but similar in appearance to a threatened species), XE (experimental essential), and XN (non-existential population)

- Species at Risk Act (SARA): Entered Canadian law on December 12, 2002, it is designed to enact provisions outlined in CITES, by the designation of the COSEWIC.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) or Comité sur la situation des espèces en péril au Canada (COSEPAC): An independent committee of wildlife experts and scientists that identifies species at risk in Canada: it designates X (extinct), XT (extirpated in Canada), E (endangered), T (threatened), SC (special concern), and NAR (not at risk).

- Canada Wildlife Act: It specifies requirements for a geographic area in Canada to be designated a National Wildlife Area by the Canadian Wildlife Service division of Environment Canada. "The purpose of wildlife areas is to preserve habitats that are critical to migratory birds and other wildlife species, particularly those that are at risk." Further, the Wildlife Area Regulations, a component of the Canada Wildlife Act, identifies activities which are prohibited on such areas because they may harm a protected species or its habitat. In some circumstances, land use permits may be granted to individuals, organizations, or companies if the intended use is compatible with conservation of the area. Personal activities such as “hiking, canoeing, photography and bird watching can be carried out without a permit in most areas”.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS): Dedicated to the management of fish, wildlife, and natural habitats, it is an organization within the US Department of Interior. Its mission is "working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people".

Emerging Infectious Diseases

- Snake Fungal Disease (Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola): Has caused population declines in snakes throughout the Midwest and eastern US. It causes a white cloudiness in eyes, thickening of the scales or skin, scabs, abnormal molting (due to fluid-filled vesicles that form between the old and new skin), and facial disfiguration that can cause emaciation and death. It is probably spread via direct contact with other infected snakes or from the natural presence of the fungus in the environment.

- Chytrid Fungus/Chytridiomycosis (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, Bd): This fungus, first discovered in 1998, grows by using amphibian skin as a nutrient, which can be especially devastating since many amphibians rely on their skin for respiration.

Ecology

- Evolution: The gradual change in genetic material of a population

- Natural selection: The breeding for specific traits by the environment

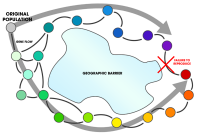

- Speciation: Formation of a new species

- Reproductive isolation: When two populations can no longer interbreed

- Ring species: When two populations that cannot interbreed are living in the same region and connected by a geographic ring of populations that can interbreed: See diagram.

- Biodiversity: The variety life in the world or an ecosystem

- Riparian: Living or located adjacent to a waterbody

- Nearctic: A biogeographic province, the northern part of the New World, includes Greenland, the Canadian Arctic islands, and all of the North American as far south as the highlands of central Mexico.

- Endemic/precinctive: The ecological state of a species being unique to a defined geographical location

- Cosmopolitan distribution: Range extends across all or most of the world in appropriate habitats

- Ephemeral: Having a short life cycle

- Perennial: (Of a plant) living for several years, generally bloom for one season, (of a stream or spring) flowing throughout the year

- Annual: (Of a plant) dying every winter, produce more flowers over more time

- Asl/Amsl: Above (mean) sea level

- Masl/Mamsl: Meters above (mean) sea level

Anatomy of Major Groups

This section is incomplete. |

- Anatomy: Bodily structure of animals

- Morphology: Form of animals and the relationships between structures

- Physiology: Normal functions of living organisms and their parts

- Bilateral symmetry: Looks the same on both sides of an axis

- Radial symmetry: Looks like a pie, can be cut in to roughly identical pieces

- Spherical symmetry: Resulting parts look the same if cut through the center

- Asymmetry: When symmetry is incomplete or not present

- Dorsal: Upper side/back

- Ventral: Underside/abdomen

- Anterior: Front

- Posterior: Behind

- Superior: Above

- Inferior: Below

- Sexual dimorphism: When two sexes of the same species exhibit different characteristics beyond the differences in their sexual organs: the opposite is monomorphism

Turtles

- Carapace: Upper shell of turtle

- Plastron: Lower shell of turtle

- Bridge: Connects carapace and plastron

- Keel: Central ridge

- Straight carapace length (SCL): Length of the turtle’s carapace measured with a pair of large calipers

- Scute: Thickened horny or bony plate

General Advice

- If the current year's rules allow either a field guide or a binder, make a binder. Binder pages can be tailored to the list, and many field guides do not contain all of the required information about each group. Typing personalized notes also increases familiarity with the information and decreases the time that it may take to complete a test.

- Print out anatomy diagrams for each major group (crocodilians, turtles, lizards, snakes, frogs/toads) and put them in their respective section of the binder. General vocabulary may also be valuable to have.

- Use tabs in a binder to find major sections easily. Post-it notes are good for this.

- Use the binder frequently, and become comfortable with finding information in it. This makes moving through the test much easier, as it means less time is spent flipping through all the pages when trying to find something quickly.

- Summarizing information is also recommended, as it finding information faster and easier.

- If a field guide is used as a source of information, keep in mind that some field guides will only have the Western specimens and some will only have the Northeastern. Be sure to know both Western and Northeastern specimens, along with Central.

- Be able to identify quickly and by scientific name. A binder should only be relied on for identifying groups that are difficult to differentiate, such as Chrysemys versus Pseudmys.

- Make flashcards (using Quizlet or a similar service) to practice identification. Always put the scientific name of each organism on the back of the flash card - this makes it easier to remember scientific names without having to sit down and memorize them.

- Some tests will also require identification of sounds. These will mostly be frog/toad calls, but other vocalizations, such as gecko squeaking or crocodilian bellowing may be used. In the 2018 and 2019 seasons, students were required to identify frog/toad calls to the species level, which is more specific than what the rules require for photo identification. A digital flash card software may also be used to memorize the calls of common frog/toad species.

Day of the Event

- Avoid panicking. This can result in unnecessary mistakes and slow down progress.

- Bring extra writing utensils in case one is misplaced or breaks.

- Talk slowly and quietly so that other teams do not hear.

- Write neatly and legibly.

- If the test is being run as stations, ensure that each answer is under the correct station on the answer sheet.

- Avoid spending more than half of the time at a station attempting to identify the specimen. If possible, move on and use logic to determine the answer to the questions.

Sample Questions

- Identify the family and genus that this lizard belongs to.

- What kind of teeth does this species of lizards have?

- Are these lizards principally herbivores or carnivores?

- Identify the family and genus that this lizard belongs to.

- What is unique about the way certain species of this lizard produce?

- What do these lizards eat?

References

- National Audubon Society Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: North America

- Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Fourth Edition; Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians

Further Reading

- 2019 National Herpetology List

- 2018 National Herpetology List

- Amphibian Embryology Webpage

- Note: This website was designed in 2002. As a result, some information may be out of date and other features may not function in modern browsers.

- Frog Call Quiz

- Identifying Californian Amphibians and Reptiles

- Detailed Information on Limited Taxa

- Center for North American Herpetology website